Xochi Magazine.

Interview with João Marques – Part Two: A Connection to the Earth

Author

Luc Levez

Featured Artist

João Marques

Published

May 2025

Share

A Connection to the Earth

Your work is deeply tied to the earth, both literally and symbolically. You often cite terra as a central theme—what does terra mean to you?

Terra has many meanings. It can mean “earth” as in the planet, or the ground we walk on. For me, it’s not the planet as a whole, but more the idea of something that supports us—something we grow from and that shapes us, and that we also try to shape in return. We adapt to it, and it forces us to readapt.

There’s a Portuguese thinker, José Mattoso, who writes about how the land grounds us, how it molds us—physically and culturally. You can see that everywhere, in how people interact with the land differently depending on their location or background. That really interests me. The idea of territory. I think I’m very much shaped by where I’m from. It’s a deep relationship I’ve only recently begun to explore more intentionally.

You mentioned being deeply influenced by where you were brought up. Are there memories from your childhood that still resonate in your work today?

I think so. I don’t directly reference my childhood in my work, but the relationship I’ve had with nature throughout my life definitely plays a role. My younger brother was always the one who was more physically involved with the landscape—climbing trees, building things. I was more of an observer, appreciating the aesthetics, the atmosphere. He was very hands-on. I was more still, watching and absorbing things in a different way.

I had a good childhood. But maybe as you get older, you start to see how fragile that world is. With the chaos we’re seeing now—the fires, the loss of habitat—there’s this growing fear of losing what I once had.

Fires and loss

You told me there was a major fire near where you grew up.

Yes. That’s why I say my work is tied to recent memories more than to childhood ones. I was in Lisbon at the time, but we saw on the news that the fire was getting closer and closer. I had to go. The firemen wouldn’t let me near my house at first, but eventually we found another way around. We were really scared. The fires lasted a week and passed through all the places that were important to me. And the thing is—it keeps happening. Friends and family talk about fires from 10 or 20 years ago. They just repeat. It’s a cycle. Devastating, over and over again.

What kind of emotions does that bring up for you?

All of them. Sadness, anger, helplessness. I remember once seeing smoke while heading to a guitar class—there was a fire just starting, and it had clearly been set on purpose. There were exploded gas canisters. That’s what angers me most—how deliberate it was. I tried to help put it out. I burned my shoes and my clothes. People came with buckets, tractors with earth—but even when the fire starts small, it gets out of control so quickly. And there’s so little you can do.

During that time, I found it hard to paint. I had to process everything.

Would you say these events transformed your artistic style? Or were you already working with these themes before?

A bit of both. I was quite young, just finishing my bachelor’s, and at that time my work was very technical. Then during COVID, we were all stuck indoors. I stayed at my parents’ house, which is surrounded by nature. That’s when I started drawing and working from the natural environment around me.

And those early works—they were greener, more full of life?

Yes, exactly. There’s a series we talked about before—four drawings, very green, very lush. I actually won the National Young Artists competition with them.

But after the fires, your work clearly darkened.

Yes, and not just because of the fires. That summer, the fires happened—but earlier that same year, in January, my brother committed suicide. Those two events together completely changed me. Since then, everything has shifted.

I used to do illustrations to earn some money. People would ask for children’s books, that sort of thing. But I felt like I couldn’t do that anymore. My palette changed. My feelings changed. I grew darker.

Do you see your work now as a form of healing?

Maybe not healing, exactly. But it’s definitely a way to express what I’m feeling. Especially my irritations—particularly when I make work about the burned lands.

Ideas vs Emotion

Would you say your art is led by emotion or by idea?

Both. I usually start with an idea, but during the physical process of creating the work, accidents happen. Emotions surface. I rarely have a fixed image in my head—it’s more of a feeling or a hunch. And what’s interesting is how things just flow. Most of the time, I don’t like what I’m doing. I really don’t—I often hate it. But I keep going. The accidents, the feelings, the movements, the music I’m listening to—it all becomes part of the work.

I usually have to step away from it, leave it for a while. Come back. Sometimes I think it’s finished but I still don’t like it, so I set it aside or break it into fragments.

So how do you know when a piece is finished?

When I’m exhausted—when I can’t think of any other way to resolve it. That usually means it’s done.

But it depends. Some works are never really finished. Others I can tolerate and let them be. It’s tied to this constant critical thought—that I should always expect more. And that can push me to keep going, to try and do better with the next one.

Paradise below

One of the things you’ve said before is that paradise isn’t above—it’s below. Can you expand on that?

Yes, that’s a kind of provocation. People are always looking up—when we seek answers, we look to the sky, to something divine, something beyond. I don’t know when that started, but it’s like we expect meaning to come from above. So this idea of paradise being below—it’s a way to challenge that assumption.

It ties back to the earth, to the ground. The material, physical part of life. What if, instead of looking up for answers, we tried looking down? To the soil, the roots, the thing that actually sustains us? That’s something I’m trying to explore more and more in my work—the gesture of looking down. Because we’re always focused on what’s around or above us, but we rarely pay attention to what’s under our feet.

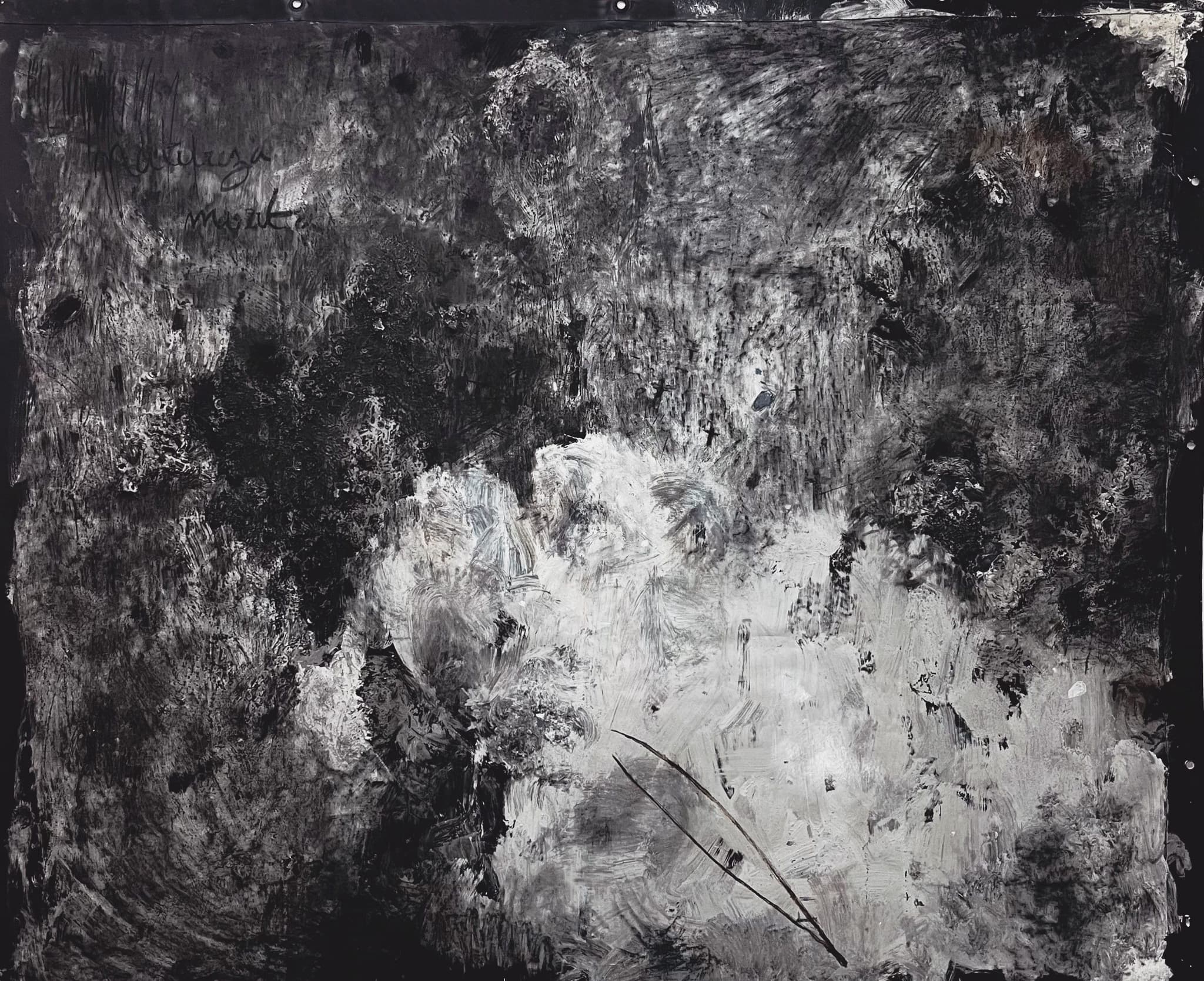

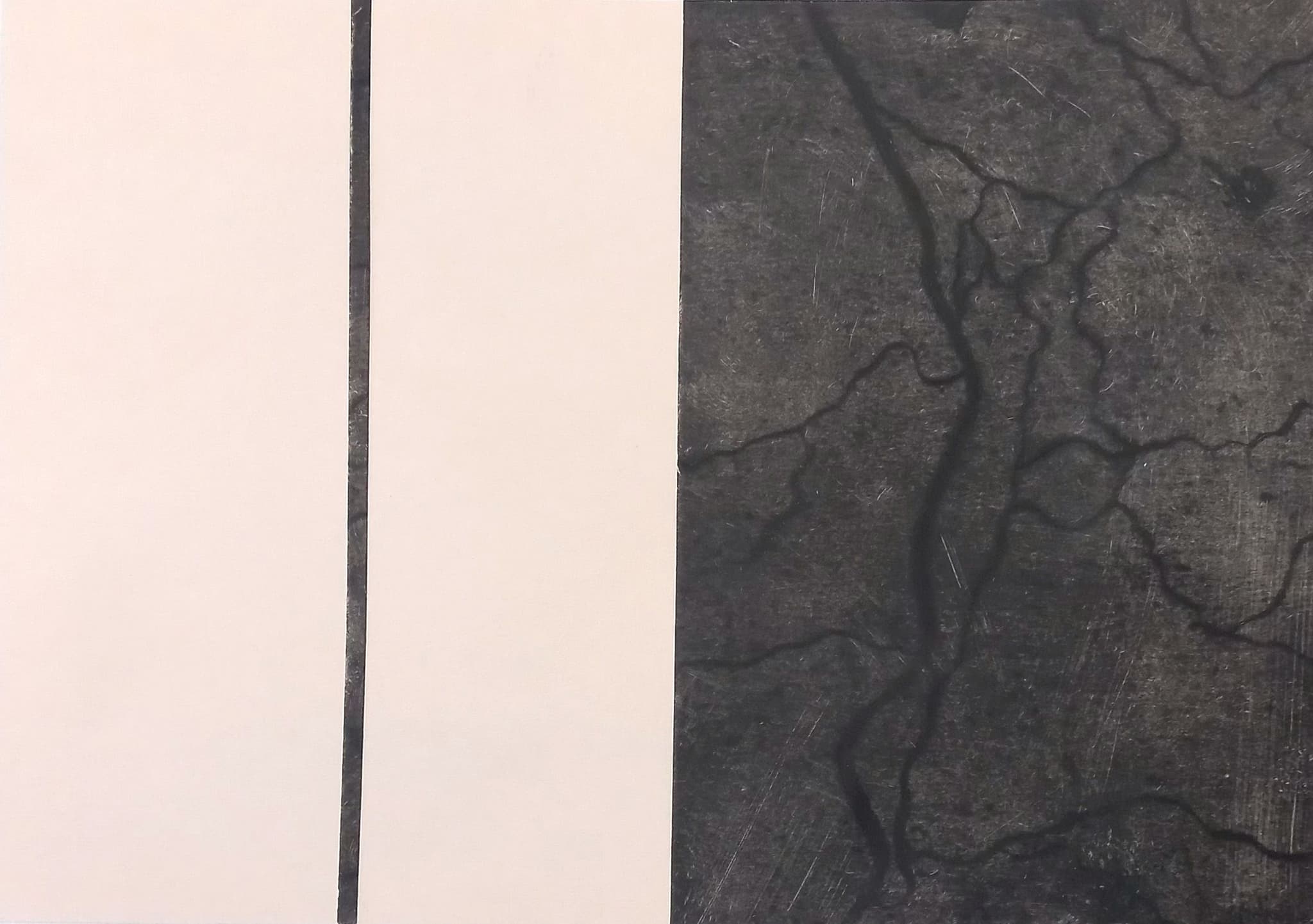

In my natureza morta pieces, that’s part of the thinking—they’re visions from above, but of the ground. Same with my Cartografias de Incêndio—a kind of mapping, a bird’s-eye view that still focuses on the earth, on what’s been damaged and what remains.

There’s this common idea that when we die, we go to heaven. But in reality, we return to the earth. And that idea became really clear to me when I was writing my master’s thesis. I had to structure everything—my thoughts, my art—and suddenly it all made sense. It was very obvious, actually, and finding a way to express that through my work—it brought me a lot of joy.

Part One: From Walk to Inspiration

Part Three: An Unexpected Connection

Never miss a Feature.

Exhibitions • Interviews • News

Est. 2024

Available Works by

João Marques

Auto-relato ou um panfleto turístico de Lisboa I

500 €

João Marques

Cartografias de um incêndio IV

350 €

João Marques

Cartografias de um incêndio III

350 €

João Marques

Cartografias de um incêndio II

350 €

João Marques

Natureza-morta III

3.000 €

João Marques

Quinto

700 €

João Marques